Little, Brown & Co.

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

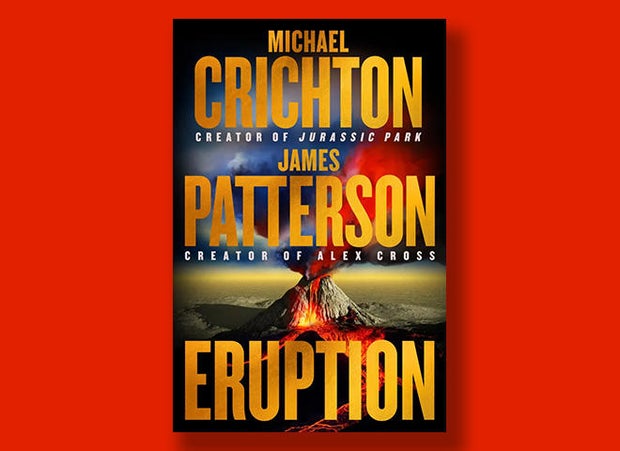

“Eruption” (to be published June 3 by Little, Brown & Co.), Michael Crichton’s thriller about a massive volcanic eruption in Hawaii, was unfinished when the “Jurassic Park” author died in 2008; more than 15 years later, James Patterson, the bestselling author behind the Alex Cross series, has completed Crichton’s work.

Read an excerpt below, and don’t miss Tracy Smith’s interview with James Patterson and Sherri Alexander Crichton (Michael’s widow) on “CBS Sunday Morning” June 2!

“Eruption” by Michael Crichton and James Patterson

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

A helicopter appeared in the window of the data room at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, frighteningly close and low; it rushed past them and swooped down into the caldera.

“Sweet Jesus!” lead programmer Kenny Wong yelled, running to the window to get a better look.

“Get the tail number,” John MacGregor, scientist in charge of HVO, snapped, “and call Hilo ASAP. Whoever that idiot is, he’s going to give one of the tourists a haircut!” He went to the window and watched as the helicopter dropped low and thumped its way across the smoking plain of the caldera. The pilot couldn’t be more than twenty feet above the ground.

Beside MacGregor, Kenny watched through binoculars. “It’s Paradise Helicopters,” he said, sounding puzzled. Paradise Helicopters was a reputable operation based in Hilo. Their pilots ferried tourists over the volcanic fields and up the coast to Kohala to look at the waterfalls.

Mac shook his head. “They know there’s a fifteen-hundred-foot limit everywhere in the park. What the hell are they doing?”

The helicopter swung back and slowly circled the far edge of the caldera, nearly brushing the smoking vertical walls.

The woman in charge of the volcano alert levels, Pia Wilson, cupped her hand over the phone. “I got Paradise Helicopters. They say they’re not flying. They leased that one to Jake.”

“Is there any news at the moment I might like?” Mac said.

“With Jake at the controls, there is no good news,” Kenny said.

“Apparently Jake’s got a cameraman from CBS with him, some stringer from Hilo,” Pia said. “The guy’s pushing for exclusive footage of the new eruption.”

“Hey, Mac? You’re not going to believe this.” She flicked on all the remote monitors at the main video panel to show the eastern flank of Kīlauea. “The pilot just flew into the eastern lake at the summit of Kīlauea.”

MacGregor sat down in front of the monitors. Four miles away, the black cinder cone of Pu’u’ō’ō — the Hawaiian name meant “Hill of the Digging Stick” — rose three hundred feet high on the east flank. That cone had been a center of volcanic activity since it erupted in 1983, spitting a fountain of lava two thousand feet into the air. The eruption continued all year, producing enormous quantities of lava that flowed for eight miles down to the ocean. Along the way, it had buried the entire town of Kalapana, destroyed two hundred houses, and filled in a large bay at Kaimūī, where the lava poured steaming into the sea. The activity from Pu’u’ō’ō went on for thirty-five years — one of the longest continuous volcanic eruptions in recorded history — ending only when the crater collapsed in 2018.

Tourist helicopters scoured the area looking for a new place to take pictures, and pilots discovered a lake that had opened to the east of the collapsed crater. Hot lava bubbled and slapped in incandescent waves against the sides of a smaller cone. Occasionally the lava would fountain fifty feet into the air above the glowing surface. But the crater containing the eastern lake was only about a hundred yards in diameter—much too narrow to descend into.

Helicopters never went inside it.

Until now.

MacGregor said, “Do we know gas levels down in there?” Near the lava lake, there would be high concentrations of sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. MacGregor squinted at his monitor.

“Can you see if the pilot’s got oxygen? ‘Cause the cameraman sure doesn’t. Both these idiots could pass out if they stay there.”

“Or the engine could quit,” Kenny said. He shook his head. “Helicopter engines need air. And there’s not a lot of air down there.”

Jenny Kimura, head lab scientist in charge of the lab, said, “They’re leaving now, Mac.”

As they watched, the helicopter began to rise. They saw the cameraman turn and raise an angry fist at Jake Rogers. Clearly he didn’t want to leave.

That meant Rogers’s passenger was even more reckless than he was.

“Go,” MacGregor said to the screen as if Jake Rogers could hear him. “You’ve been lucky, Jake. Just go.”

The helicopter rose faster. The cameraman slammed the door angrily. The helicopter began to turn as it reached the crater rim.

“Now we’ll see if they make it through the thermals,” MacGregor said.

Suddenly there was a bright flash of light, and the helicopter swung and seemed to flip onto its side. It spun laterally across the interior and slammed into the far wall of the crater, raising a tremendous cloud of ash that obscured their view.

In silence, they watched as the dust slowly cleared. They saw the helicopter on its side, about two hundred feet below the rim, resting precariously at the edge of a deep shelf below the crater wall, a rocky incline that sloped down to the lava lake.

“Somebody get on the radio,” Mac said, “and see if the dumb bastards are alive.”

Everyone in the room continued to stare at the monitors. Nothing happened right away; it was as if time had somehow stopped moving when the helicopter did. Then, as they watched, a few small boulders beneath the helicopter began to trickle down. The boulders splashed into the lava lake and disappeared below the molten surface.

More rocks clattered down the sloping crater wall, then more —larger rocks now —and then it became a landslide. The helicopter shifted and began to glide down with the rocks toward the hot lava. They all watched in horror as the helicopter continued its downward slide. Dust and steam obscured their view for a moment, and when it blew away, they could see the helicopter lying on its side, rotor blades bent against the rock, skids facing outward, about fifty feet above the lava.

Kenny said, “That’s scree. I don’t know how long it’ll hold.”

MacGregor nodded. Most of the crater was composed of ejecta from the volcano, pumice-like rocks and pebbles that were crumbly and treacherous underfoot, ready to collapse at any moment.

From across the room, Jenny said, “Mac? Hilo still has contact. They’re both alive. The cameraman’s hurt, but they’re alive.”

“How much daylight do we have left?” MacGregor asked her.

“An hour and a half at most.”

“Call Bill Kamoku, tell him to start his engine,” Mac said. “Call Hilo, tell them to close the area to all other aircraft. Call Kona, tell ’em the same thing. Meantime I need a pack and a rig and somebody to stand safety. You decide who. I’m out of here in five. We wait, they die.”

*****

The red HVO helicopter lifted off the observatory helipad and headed south. Directly in front of them, four miles away, they saw the black cone of Pu’u’ō’ō, its thick fume cloud rising into the air.

Mac rechecked his equipment in his front seat, making sure he had everything. Jenny Kimura and Tim Kapaana were in the rear. Tim was the biggest of their field techs, a former semipro linebacker.

He stared out of the bubble. They were over the rift zone now, following a line of smoking cracks and small cinder cones in the lava fields. The collapsed crater of Pu’u’ō’ō was a mile ahead and just beyond it was the eastern lake.

Bill said, “Where do you want to put down?”

“South side is best.”

The helicopter set down about twenty yards from the crater rim. Immediately, the helicopter’s bubble clouded over with steam from nearby vents. MacGregor opened his door and felt air both wet and burning on his face.

“Can’t stay here, Mac,” Bill said. “I’ve got to move downslope.”

“Go ahead,” Mac said, then pulled off his headset and stepped down onto the gray-black lava without hesitation, ducking his head beneath the spinning rotor blades.

The downed helicopter was at the opposite side of them, on a shelf above the lake. But its position was even more precarious now. The lava could spin at any moment, meaning the craft was perhaps seconds away from sliding down into the lava. Mac had already zipped up his green jumpsuit. He cinched the harness tighter around his waist and legs. He could loosen it when he got down there and put it around another person.

MacGregor handed the ends of the rope to Tim. He adjusted the radio headset over his ears, pulled the microphone alongside his cheek. Jenny had put on her own headset and clipped the transmitter to her belt, and she heard MacGregor say, “Here we go.” Jenny watched as Mac descended slowly and carefully into the crater.

The lava lake was nearly circular, its black crust broken by streaks of brighter and more incandescent red. Steam issued from at least a dozen vents in the rocks. The walls were sheer, the footing uncertain; Mac stumbled and slid as he went down.

Suddenly his extended leg hit a solid surface, like he was a base runner sliding into second.

Although he was only a few feet below the rim, he could feel the searing heat from the lake. The air shimmered unsteadily in the convection of rising currents. Between that and the sulfurous odors swirling from the crater, he began to feel slightly nauseated.

As Mac descended along the sheer wall, inside his heat-resistant jumpsuit, he was sweating. Thin Mylar-foam insulation sewn between layers of Gore-Tex kept sweat off the skin, because if the temperature went up suddenly, the sweat would turn to steam and scald his body, meaning almost certain death.

The helicopter hung only fifty yards above the lava lake. Below the crust, the glowing lava was around 1800 degrees Fahrenheit, and that was at the low end.

*****

“There’s a guy coming down for us.”

Pilot Jake Rogers, on his side and in a tremendous amount of pain, looked straight down at the lava lake and heard the hissing of the gas escaping from the glowing cracks. He saw spatters of lava, like glowing pancake batter, thrown up on the sides of the crater.

Jake didn’t think his leg was broken. The cameraman—Glenn something —was in worse shape, moaning in the back seat that his shoulder was dislocated. He rocked in pain, which rocked the helicopter. The sudden shift of weight sent the copter sliding downward again, throwing Jake’s head against the Plexiglas bubble.

The cameraman began to scream.

Only twenty yards away now, MacGregor watched helplessly as the helicopter began a rumbling descent. He heard yelling from inside, and it must have been the cameraman, because Jake Rogers swore at the guy and told him to shut the hell up. The helicopter slid another twenty feet toward the lava, then miraculously stopped again. The struts were still facing outward; the twisted rotors were buried in the scree. The passenger door was still facing upward.

*****

Jenny turned to Tim, covered her microphone, and said, “How long has he been down there?”

“Eighteen minutes.”

“He’s not wearing his mask. That may help him communicate clearly, but it’s going to get to him soon. We both know that.”

She meant the sulfur dioxide gas, which was concentrated near the lake. Sulfur dioxide combined with the layer of water on the surface of the lungs to form sulfuric acid. It was a hazard for anyone working around volcanoes.

“Mac?” she said. “Did you put your mask on?”

He didn’t answer.

She looked through the binoculars, saw that Mac was moving again. He was above the helicopter now, about to lean down on the bubble. She couldn’t see his face but saw straps across the back of his head, so at least he was wearing the mask.

She saw him drop to his knees and crawl gingerly onto the bubble. Mac picked up a short crowbar and started trying to pry open the door. He saw Jake pushing up on the Plexiglas from inside. He heard the cameraman whimpering. MacGregor strained against the crowbar, using all the leverage he had, until, with a metallic whang, the door sprang open wide and clanged hard against the side panel. MacGregor held his breath, praying that the helicopter wouldn’t begin to slide again.

It didn’t.

Jake Rogers stuck his head up through the open door. “I owe you, brah.”

“Yeah, brah, you do.” MacGregor reached out a hand, and the pilot grabbed it and clambered onto the bubble. Once he was out, MacGregor saw that his left pants leg was soaked in blood; it was smeared all over the Plexiglas dome.

MacGregor asked, “Can you walk?”

“Up there?” Jake pointed to the rim above. “Bet your ass.”

In the back, the photographer was huddled in a ball at the far side of the helicopter. Still whimpering. A haole guy, late twenties, skinny, his face the color of paste.

“He got a name?” Mac asked Jake.

“Glenn.” Jake was already starting up the slope.

“Glenn,” MacGregor said. “Look at me.”

The cameraman looked up at him with vacant eyes.

“I want you to stand up,” MacGregor said, “and take my hand.”

The cameraman started to stand, but as he did, the lava lake below began to burble, and a small fountain spit upward with a hiss. The cameraman collapsed back down and started to cry.

*****

Over the headset, Mac heard Jenny say, “Mac? You’ve now been down twenty-six minutes. Glenn and Jake already have pulmonary restriction. You’ve got to get out of there before you do.”

“I got this,” MacGregor said, looking at the lake through the bubble. Everything he’d learned from everywhere he’d been in the world of volcanoes told him he wasn’t fine at all.

“We’re gonna die here!” Glenn yelled, tears streaming down his cheeks.

“Just hang on,” Mac barked.

Then he climbed down into the helicopter.

The helicopter slowly rotated on its axis. Mac gripped the seat, trying to keep his balance, watching helplessly as the world outside spun, the Plexiglas bubble closer than ever to the glowing surface. Then it stopped, and the Plexiglas started to blister and melt, and smoke filled the interior of the helicopter.

“Just try to keep your balance so you don’t jar this thing,” Mac said.

The cameraman stepped between the seats, coughing because of the smoke, moving as if in a daze.

They were just a few feet above the lava lake. Small sparks were spattering up. MacGregor stepped out, drew Glenn after him.

He tried to ignore the smell of fuel.

Nearly out of time.

Glenn followed him outside.

“You got this,” Mac said, steadying him as his feet slid.

“I’m scared of heights,” Glenn said, keeping his eyes fixed on the rim of the crater, away from the lava.

MacGregor thought: You should have thought of that before, you jackhammer.

Mac looked up, saw Jake about ten yards above them, reaching for Tim. Down here, the sharp odor of aviation fuel was stronger than ever.

They kept moving. The guy looked around and said, “Hey, what’s that smell?”

Too late to lie to him, too close to the top. “Fuel,” John MacGregor said.

His radio crackled, and he heard Jenny say, “Mac, the lab says the concentration from the fuel vapor is going up.”

Mac looked back and saw the Plexiglas bubble of the helicopter had begun to burn; flames licked upward along the fuselage.

His headset crackled again. “Mac, you’re out of time—”

But in the very next moment Tim was grabbing Glenn in his big arms and pulling him over the side. He quickly did the same for Mac, who glanced back and saw the helicopter enveloped in flames. Glenn tried to move back to the crater, but Tim shoved him hard toward their copter.

“We’re safe now,” the cameraman said. “What’s the freaking rush?”

The helicopter exploded.

There was a roar, and the force of the explosion nearly knocked them all to the ground. A yellow-orange fireball burst up beyond the crater rim. A moment later, hot, sharp metal fragments clattered onto the slope all around them as they hurried to the red HVO helicopter.

From “Eruption.” Copyright © 2024 by Michael Crichton and James Patterson. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.

Get the book here:

“Eruption” by Michael Crichton and James Patterson

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info: